DAM Pilot Missions

Exclusion of bottom trawling in protected areas of the North Sea and Baltic Sea

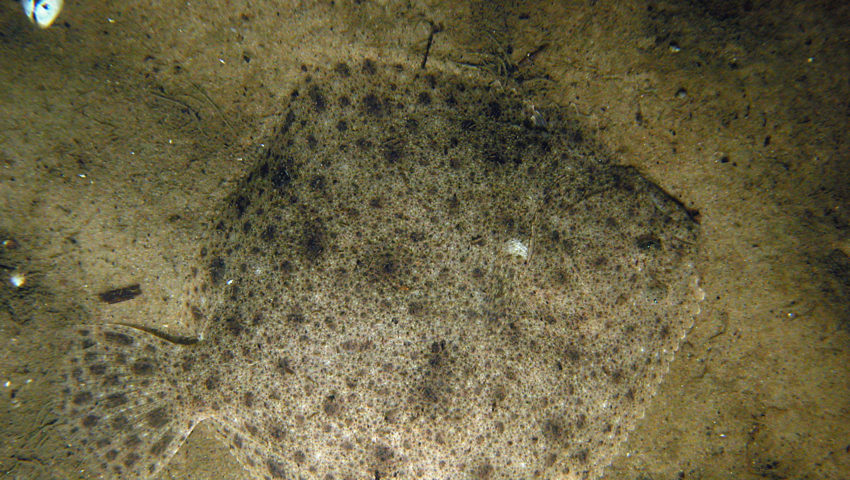

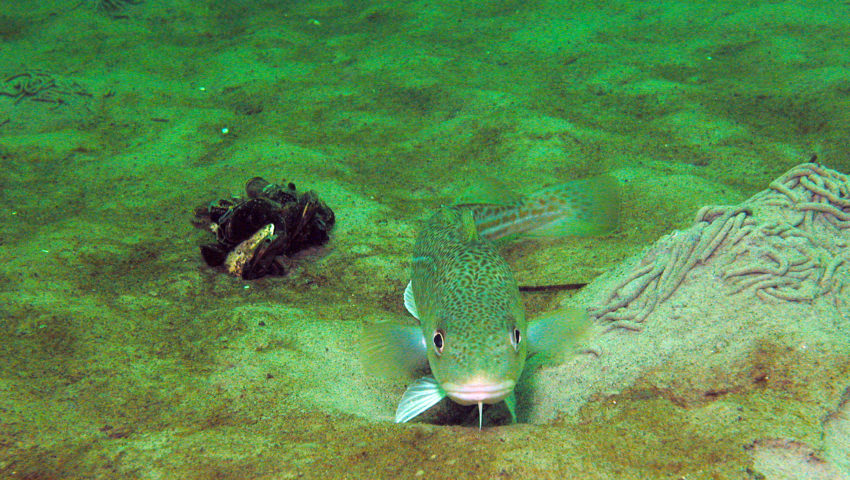

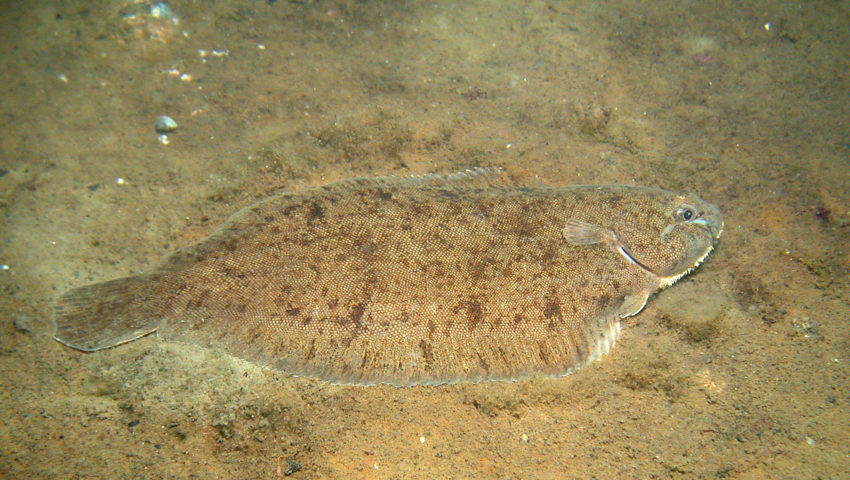

Shrimp, plaice, sole, turbot and cod are in great demand on our dinner tables. However, catching them can impair benthic habitats and cause large numbers of juvenile fish and other marine life to become by-catch.

Mobile bottom-contact fishing uses various types of bottom trawls: in beam trawling, a wooden or metal crossbar holds open the net, sliding across the seabed on shoes. When used to catch flatfish, the nets are fitted with tickler chains; beam trawls for catching shrimps are fitted with roller gear. Bottom trawls which are kept open horizontally by large rectangular otter boards are called otter trawls.

Pilot mission “MGF Nordsee”

Project partners:

– Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research AWI

– Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg UOL

– The Thünen Institute Thünen

– Senckenberg am Meer, Senckenberg Society for Nature Research SAM

– Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht, Centre for Materials and Coastal Research HZG

Project leader: Prof. Dr. Karen Wilshire (AWI)

Coordinator: Dr. Sabine Horn (AWI)

e-mail: sabine.horn@awi.de

Pilot mission “MGF Ostsee”

Project partners:

– Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde IOW

– University of Rostock Rostock

– Senckenberg am Meer, Senckenberg Society for Nature Research SAM

– University of Cologne Köln

– The Thünen Institute Thünen

– Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel GEOMAR

– German Research Centre for Geosciences GFZ

Project leader: Prof. Dr. Klaus Jürgens (IOW)

Coordinator: Dr. Christina Schmidt (IOW)

e-mail: christina.schmidt@io-warnemuende.de

LIFE ON THE SEABED IN THE NORTH SEA AND BALTIC SEA

CONTEXT: PROTECTION AND USE OF THE North Sea AND BALTIC SEA

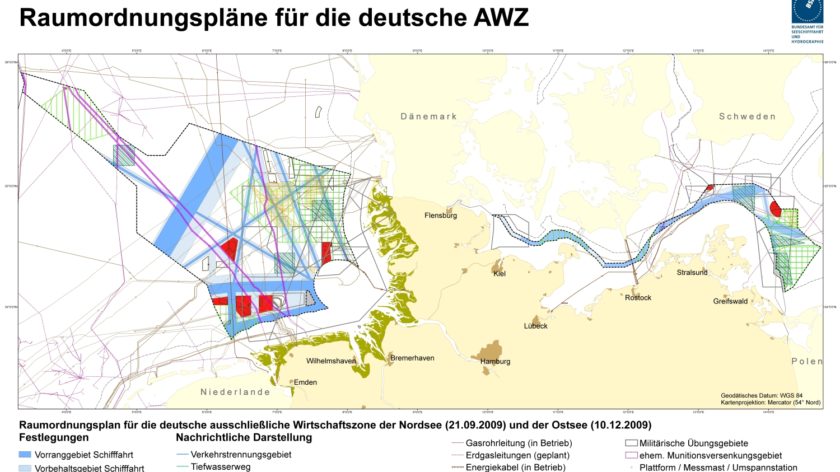

The following paragraphs provide background information on the DAM pilot missions. More specifically, they describe the protection and use of those areas of the North Sea and Baltic Sea that are part of the German Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Maritime spatial planning determines the ways in which these areas may be used and also specifies the marine protected areas. The framework for assessing the environmental status of the North and Baltic Seas is provided by the European Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Bottom trawling is one of the human uses that will be banned in the protected areas in the near future, in order to prevent negative impacts on benthic habitats.

Maritime spatial planning: Growing competition for space in oceans and seas

Advertisements for tourist destinations on the North Sea and Baltic Sea praise “the endless expanse of the sea”; but in many places, the vast horizons are interrupted by brisk shipping traffic and wind turbines. Just like on land, different ways of utilising the seas are increasingly competing for space, which is also limited in the North Sea and Baltic Sea. Shipping, offshore wind power, fishing, mining and other operations all require space, and so do the needs of environmental and nature conservation.

People spending their holidays along the coast of the North Sea and Baltic Sea can enjoy expansive views of the horizon from the beaches. Standing here, it is hard to imagine that the seas on our doorstep are among the most intensively used marine areas in the world.

Maritime spatial planning is meant to coordinate the interests of users and the needs of conservation to achieve a sustainable development of the seas. Corresponding spatial development plans are in place for the German Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the North Sea and Baltic Sea:

Marine protected areas: Conservation of ecosystems and biodiversity

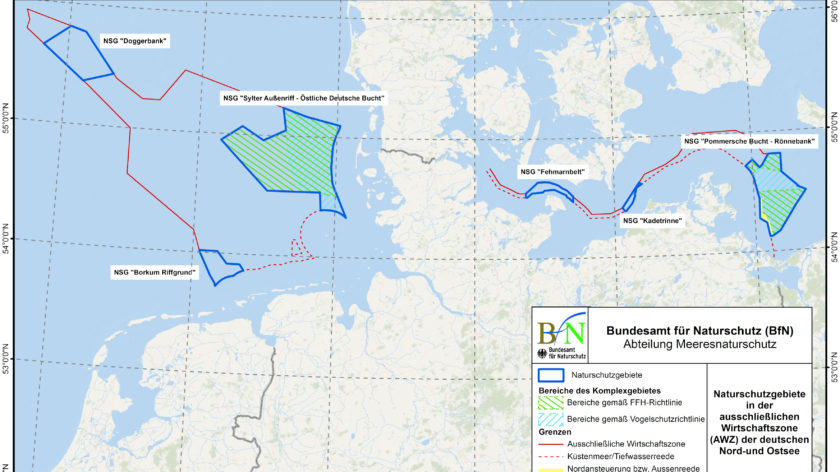

The German Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the North Sea and Baltic Sea contains six marine protected areas, which belong to the so-called Natura 2000 areas, a connected network of protected areas within the European Union. The protection of endangered wild fauna and flora in their natural habitats is governed in the Natura 2000 areas by the Birds Directive and the Habitats Directive.

The European network of protected areas, Natura 2000, aims to protect natural habitats as well as wild fauna and flora. The ten Natura 2000 areas in Germany’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the North Sea and Baltic Sea have been protected since 22 September 2017 in the form of six nature reserves:

Marine Strategy Framework Directive: Environmental status not yet good

Oceans play a central role for our climate, are among the most important ecosystems on earth, are rich in biodiversity, provide raw materials and food, serve as transport routes and offer valuable recreational areas. Seas and oceans influence human lives in many different ways. Healthy oceans, which are protected and used sustainably, are therefore of vital interest to society as a whole. The European Marine Strategy Framework Directive provides a uniform regulatory framework for the environmental status of the North Sea and Baltic Sea. It calls upon EU member states to take the necessary measures to achieve a good environmental status in the marine environment by the end of 2020, as described in that Directive.

Rubbish washed up on the beach is a visible sign of marine pollution. However, the bulk of pollution to the North Sea and Baltic Sea is invisible to us. Nevertheless, its effects can be grave.

Effects of bottom trawling

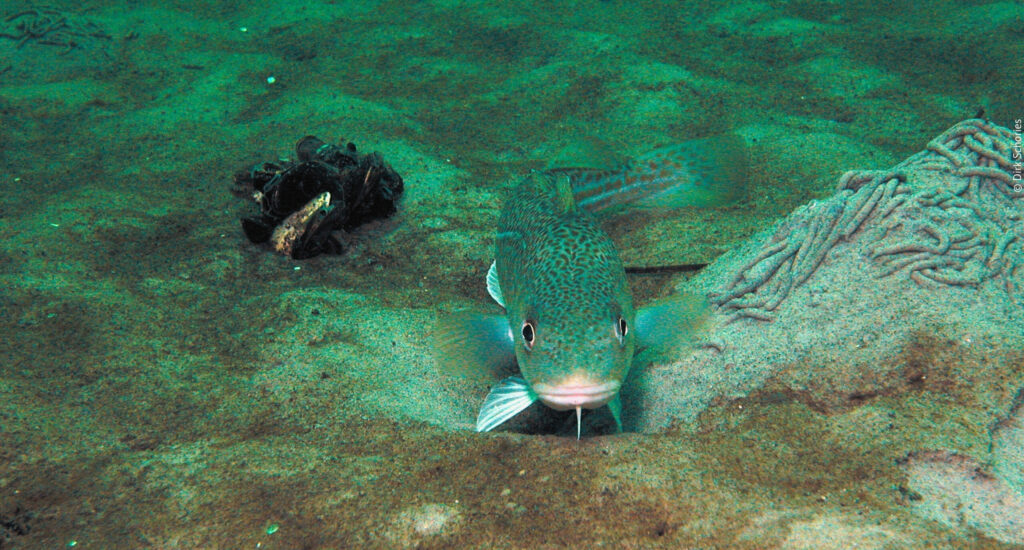

So-called mobile bottom-contact fishing uses bottom trawls to catch plaice, sole, cod and North Sea shrimp. Such fishing methods can have a significant impact on the seabed and its inhabitants, bringing them into conflict with conservation objectives. A number of different research projects have shown that intensive fishing on the seabed can have a significant negative impact on the biodiversity and composition of the communities living there.

Taking samples from the seabed: a 3-metre beam trawl on the fisheries research vessel Clupea, leaving Rostock in July 2020.

Ecosystem research and management in protected areas

At present, there are virtually no undisturbed seabeds in Germany’s North Sea and Baltic Sea areas. The DAM pilot missions therefore offer a unique opportunity to observe how marine protected areas – with their ecosystem functions and seabed biodiversity – will develop in the future if bottom trawling is discontinued. The results will provide an important basis for the future management of the protected areas in the North Sea and Baltic Sea.

Ended up in the bottom trawl: Catch for research purposes in the Fehmarn Belt, alongside a designated Natura 2000 site in July 2020. The basket contains flatfish (mainly dab, some plaice and flounder), herring and sprat, as well as a lumpfish (the greenish blue fish). Also valves of the ocean quahog.

Sorting the catch from a beam trawl off Nienhagen near Rostock in July 2020: many ocean quahogs live in the soft seabed and also end up in the net. Ocean quahogs can live to be over 30 years old in the Baltic Sea and over 200 years in the deep and cold waters around Iceland.

Analysing the size of turbot: In order to determine the status of fish stocks in the North Sea and Baltic Sea, fish are caught and measured for research purposes.

Newsletter

Always up to date with the DAM newsletter. (German only)